Letterkenny & World War 1

There is an oft-repeated phrase that ‘history is written by the winners’ and there is no doubt that the perception of Irishmen’s involvement in World War 1 was ‘changed utterly’ by the events of Easter 1916. When General John Maxwell issued the orders to execute the leaders of the short lived rebellion in our nation’s capital, the gunshots from Kilmainham Jail echoed throughout the land, resulting in a rippling groundswell of fervent Republicanism and a general antipathy towards anyone who was at that time serving in the British Army.

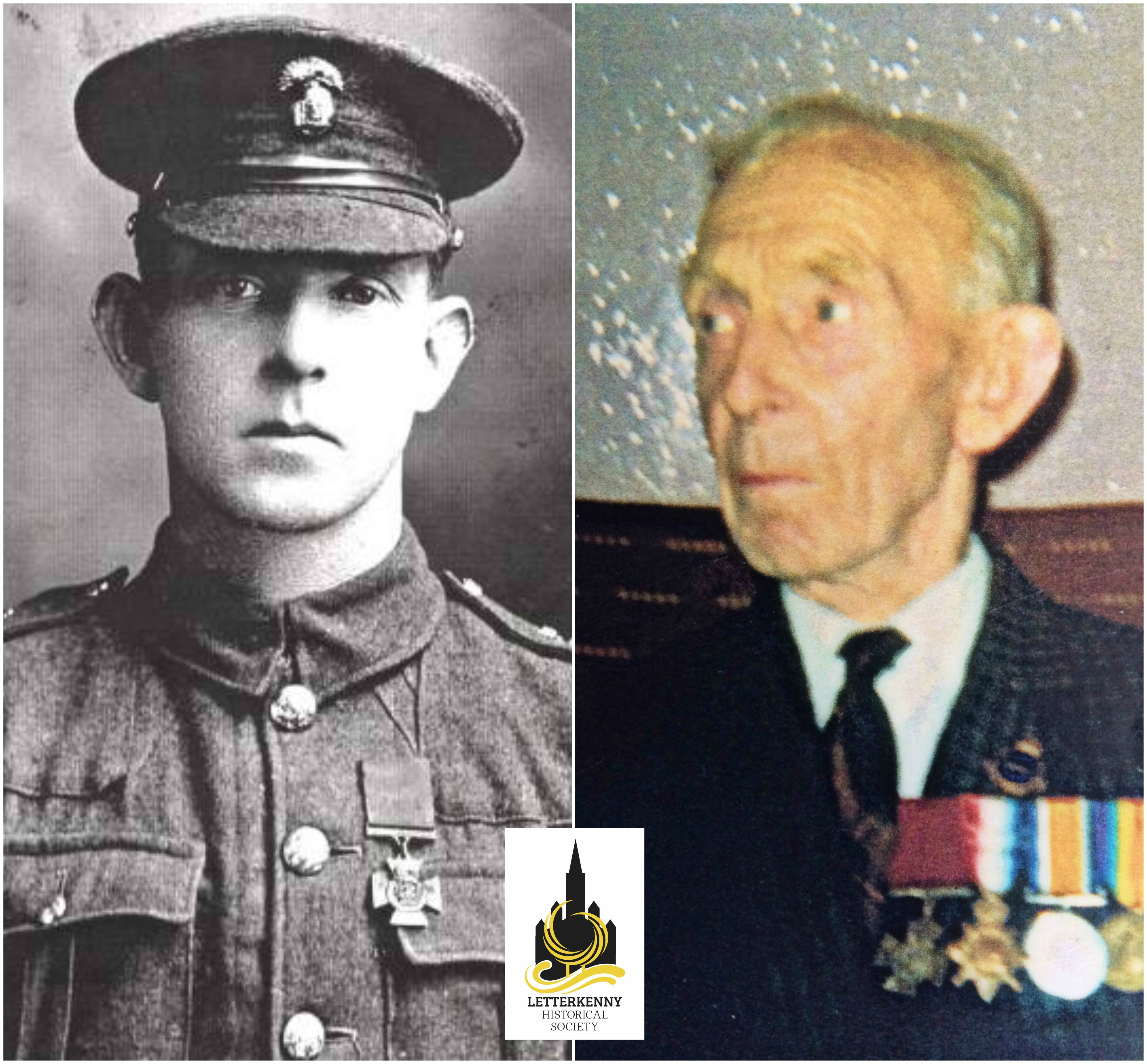

When many combatants returned home from the blood soaked trenches of Flanders and Gallipoli in 1918, they found a different nation to the one they left behind four years previously, especially in the attitudes of those that had remained at home. Many of those who returned, such as VC James Duffy, were castigated and shunned for their involvement with the British Army and over the years, chose not to talk about their experiences in the trenches for fear of reproach. As a result, a cloud of ‘collective amnesia’ concerning Ireland’s role in the war hung ominously over our country for almost one hundred years.

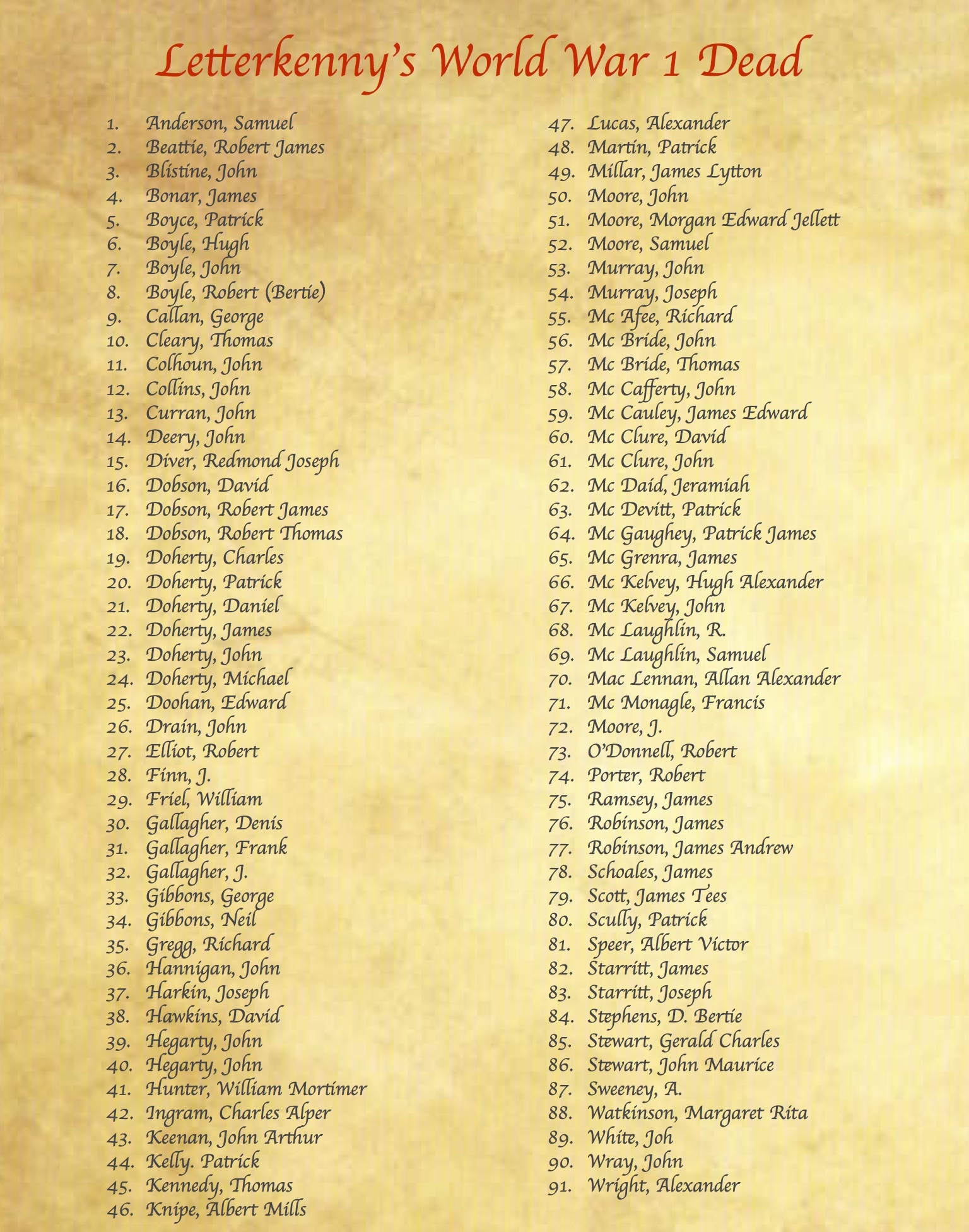

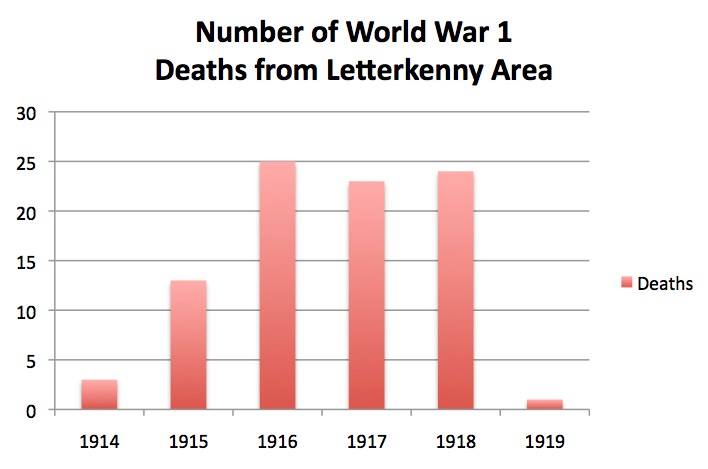

However, time, as always, has proven to be a great healer. It appears that the people of Ireland are gradually emerging from under the clouds of this ‘collective amnesia’ and most are ready to view the roles played by so many Irishmen in the war of 1914-1918 with a greater understanding. Almost 200,000 men from Ireland fought in World War 1 (plus 300,000 Irish immigrants or people with Irish parents). Of these numbers who enlisted, somewhere between 35,000 and 50,000 Irishmen never returned home, including 1,200 from Donegal and approximately 91 from the Letterkenny area.

To truly understand the motives why men from Letterkenny signed up to fight in the Great War, we must return to the Ireland of 1914 and view their world with pre-1916 eyes. This was a time of great hope and the beginning of a ‘new Ireland’ with the granting of Home Rule. The scenes of jubilation in the town of Letterkenny at this historic occasion were described in the Derry Journal:

“Every Nationalist house in the town was illuminated, most of them with great artistic taste. The green flag flew from many windows while vari-coloured bunting was general. On the Sentry Hill, Market Square, and at street junctures large bonfires blazed, and all around the town the hilltops and hillsides were lit up.”

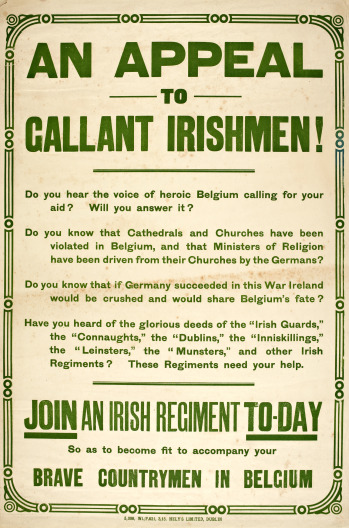

After having finally received Home Rule, there was the perception that Ireland had to prove that it was worthy of it, especially in the face of the rising resistance from Carson and the Ulster Volunteer Force. The UVF had been formed by Unionists to oppose, by force of arms, the introduction of ‘Rome Rule’ in 1913 and in response, Nationalists formed the Irish National Volunteers to protect its smooth implementation. In Letterkenny, local regiments of the UVF drilled on the Boyd’s estate at nearby Ballymacool and the National Volunteers openly paraded at Sentry Hill, albeit with camans and wooden sticks instead of rifles. When war broke out, many believed that by serving in Irish Regiments within the British Army, they could receive the necessary training to become a disciplined force to protect the rights of the people. In other words, when they signed up for the European conflict, they saw themselves not as fighting FOR Britain in the war but rather ALONGSIDE Britain as a new and independent nation.

The attitude of a moral duty to assist the plight of a fellow Catholic country was another reason why many Letterkenny men signed up to fight. When the German soldiers advanced on France in August 1914, they plundered and destroyed many towns and villages throughout Belgium, creating thousands of innocent refugees as a result. In Letterkenny, a Belgian Refugee Committee was set up to assist these refugees and on Tuesday 12th January 1915, ten Belgian families of 48 people arrived in the town, being received by Bishop Patrick O’Donnell and members of the Relief Committee at the train station. Crowds of Letterkenny people met them also and the families were taken to the Technical School on the Main Street where the committee had prepared a dinner for them. Following dinner, the families were then taken to their accommodation in the new council houses that had been built at Ballymacool Terrace, remaining for the duration of the war.

At a public meeting of the Nationalists of the Letterkenny district in the Market Square on Sunday September 27th 1914, Father John McCafferty, administrator in St. Eunan’s Cathedral, told the large assembled crowd:

“German armies of destruction are let loose on Belgium. Her churches and her homes, her libraries and Universities are destroyed, and Belgian soil is drenched with the blood of her people. If justice is to prevail, the wrongs of Belgium must be righted, and the sympathies of right-thinking men will be with her, as I am glad to think your sympathies are with her in her hour of trial and distress.”

Many from Letterkenny answered this call to arms, whether they were living at home or employed in seasonal work in Scotland. One of the most notable locally was James Duffy from Bonagee, who was one of only 37 Irishmen who received the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest military decoration awarded for valour in the face of the enemy, when he rescued two men from certain death under heavy gunfire in Palestine in 1917.

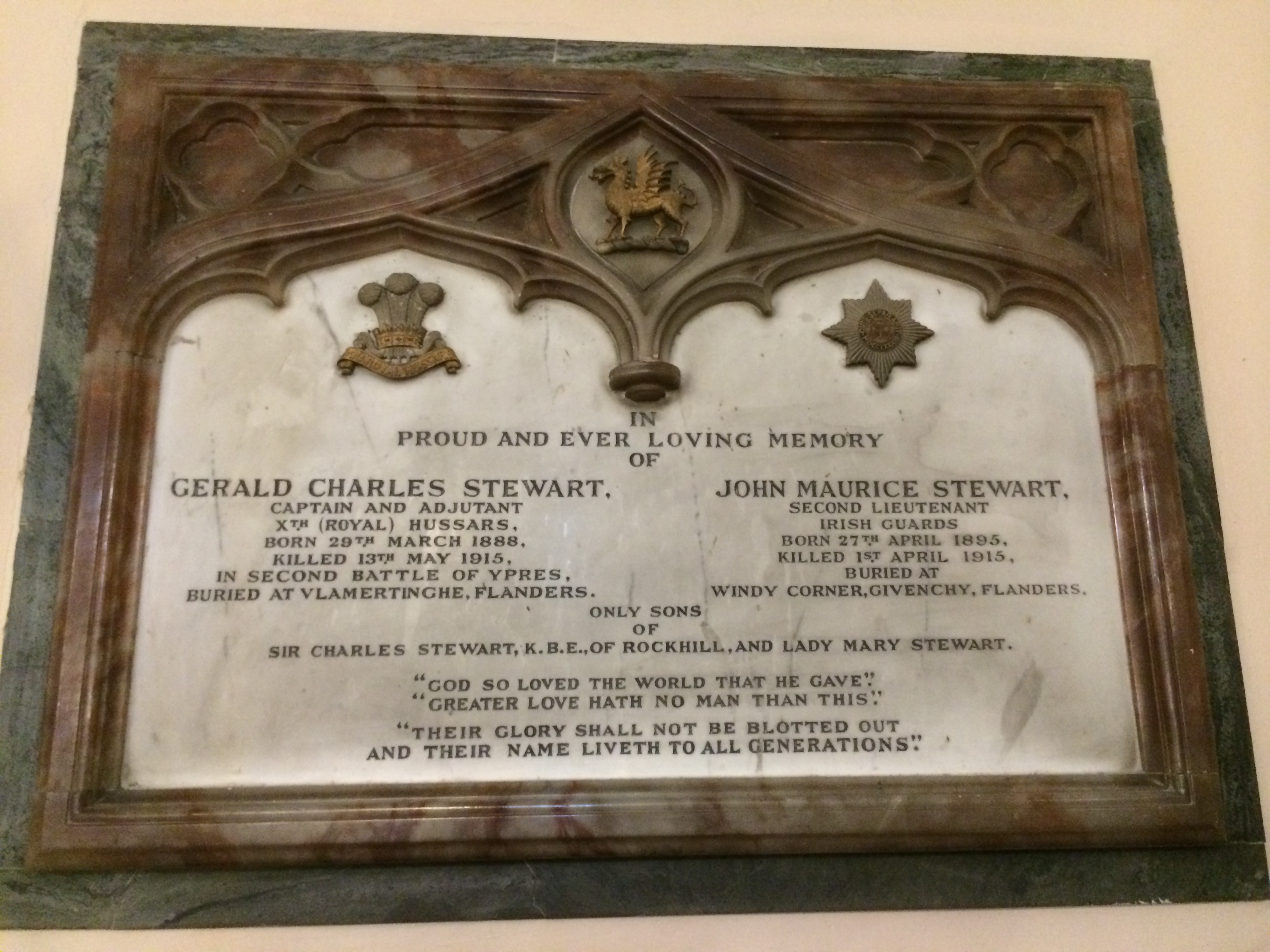

In total, almost 170 men from the Letterkenny area signed up to fight in World War 1 with 91 (that we know of) losing their lives. Eight men from the town died in the Battle of the Somme, four of them on the very first day of the battle. From what we know, fifty Letterkenny men are buried in France, twenty-one in Belgium and eight in Turkey. Many men from the same family enlisted and lost their lives also such as David and Robert Dobson from Ballymacool, Charles and Paddy Doherty from Asylum Road, Hugh and John McKelvey, Charles and John Stewart of Rockhill House and Daniel, James and John Doherty from Sentry Hill. These last three names are noticeable in that, similar to the Hollywood movie “Saving Private Ryan”, only one of the four Doherty brothers who enlisted – William – was able to return home alive.

The names of those that lost their lives are forever preserved through the continued efforts of the County Donegal Book of Honour Committee while a brass plaque containing the names of many of those from the parish that survived hangs proudly in Conwal Church (see picture below). In August 2014, the Letterkenny Community Heritage Group commissioned a sculpture near the Cathedral Square in memory of those from the Letterkenny district who lost their lives. Local artist Redmond Herrity whose great-grandfather (Barney Sweeney) had fought in the War designed it while Paddy Harte (on behalf of his father) and Johnny Keys (grand-nephew of the Doherty brothers of Sentry Hill) unveiled the sculpture to a large crowd of almost 200 people while the names of the dead were read out. There was a calm solemnity amongst the assembled crowd that evening with many people somewhat surprised to learn of the indelible connections that the town has with the war. One person, for example, heard their great granduncle’s name being read out and never knew that he had died in the war.

However, despite these recent renewed efforts at recognizing the thousands of Irishmen who served in the war of 1914-1918, the attitudes of many Irish people towards those that served sadly remains. In their eyes, these men served in the British Army, the army of the ‘enemy’, simple as that. Many people unfortunately still share Sir Roger Casement’s attitude that they were ‘not Irishmen but English soldiers’, their views and attitudes being molded and shaped by years of misunderstanding as to the true motives of those that fought. This attitude was noticeable when the beautiful monument to the Letterkenny men and women at Cathedral Car Park was vandalized in 2017. It was replaced with a smaller monument, but sadly that too was vandalized but thankfully it was replaced once more earlier this year and a monument to these Letterkenny men and women now stands once again in the town.

From our post-1916 viewpoint, it is difficult to imagine the emotions that prevailed in the country in 1914. They were not to know what would happen two years later. At long last Ireland had received Home Rule, an occasion that their fathers and grandfathers did not witness. O’Connell, Butt and Parnell had each tried and failed to implement a Repeal of the Union with Britain but each had failed. Now though, Redmond had succeeded. It was a ‘new Ireland’. Those that served would receive the necessary training and discipline that would be implemented in a new Irish army after a war that they were told would ‘be over by Christmas’. They believed that if Home Rule was to be successfully implemented following the war, the State would need an efficient army to combat the threat of Carson and the UVF and avoid a partition of the country. Serving in the war would also show that Ireland was an ally of Britain, not an enemy, and that we could be trusted in our new found situation. This was the viewpoint of many people from the town of Letterkenny and in Ireland as a whole when they signed up so readily in 1914.

Several days after the outbreak of the war, the Derry Journal from Friday August 7th1914, gives us an interesting pre-1916 perspective of the Irish Nationalists in Dublin:

“Probably never in the history of Dublin were such scenes presented as those at the North Wall, when several hundred reservists left for Holyhead. Fully 50,000 people, drawn from all classes, thronged the quays. The vast majority were working class people whose husbands, fathers or brothers were leaving for the front…During the waiting hours the crowd sang national songs, and a band played “A Nation Once Again.”

However, those men that left for the front in 1914 amidst great cheers from the people returned to a new Ireland just four years later. After the war, some wasted no time in joining the Volunteers, whose name was by now changed to the Irish Republican Army, and fought against the British army in the War of Independence, such as Charlie ‘Bovril’ Collins. Many others didn’t join up however, having seen enough bloodshed and battle on the war fields of Europe. Those who had served in the British Army were commonly branded traitors and ‘not Irish’ in the new zeal of republicanism that came following the General Elections of 1918. Most retreated under a veil of silence and refused to talk about their horrific experiences in the trenches with many taking their unresolved pain to their graves, unable to communicate their feelings with even their closest family relatives.

However, today, one hundred years since the guns fell silent, more than ever these men now deserve to be honoured and remembered. Whether it was to assist Catholic Belgium or to protect a new Ireland under Home Rule or indeed whatever other personal reasons they may have had, the harrowing experiences that they went through on the battlefields of Europe might be difficult for us to comprehend today, but they should never be forgotten. It is only by understanding and appreciating the motives and experiences of those Irishmen that fought in the war of 1914-1918, that we as a modern nation can truly emerge, once and for all, from beneath the dark clouds of our past.

Dedicated to the 91 people from Letterkenny who died in World War 1. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a n-anam